Making diabetes care personal with the right data

December 8, 2017

By Darshak Sanghavi, MD, and Samantha Noderer, MA, OptumLabs

It isn’t easy being the pancreas.

Nobody understands this better than somebody with diabetes — a chronic disease impacting more than 30 million people in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. A healthy pancreas constantly checks the body’s blood glucose (sugar) levels and adjusts them from rising too high by releasing tiny bursts of insulin. In people with type 2 diabetes, the body resists that insulin and in time the pancreas cannot keep up with the demand. When glucose in the blood becomes dangerously high, it can cause damage to vital organs like the kidneys, heart, eyes, and brain over many years. That’s a lot of pressure!

When the pancreas struggles, doctors can step in to monitor a patient’s average glucose levels through a blood test called hemoglobin A1C (HbA1c). For most people with controlled type 2 diabetes, it’s recommended they’re tested 1–2 times per year.

But it turns out there’s a lot of variation when it comes to how often patients are getting their A1C tested. Some are tested more frequently than necessary. Others are not tested enough. OptumLabs® and our partners are leveraging data to help us to gain insights on how this may impact a patient’s health, and how to better manage their diabetes.

Your zip code could impact how often you’re tested for diabetes

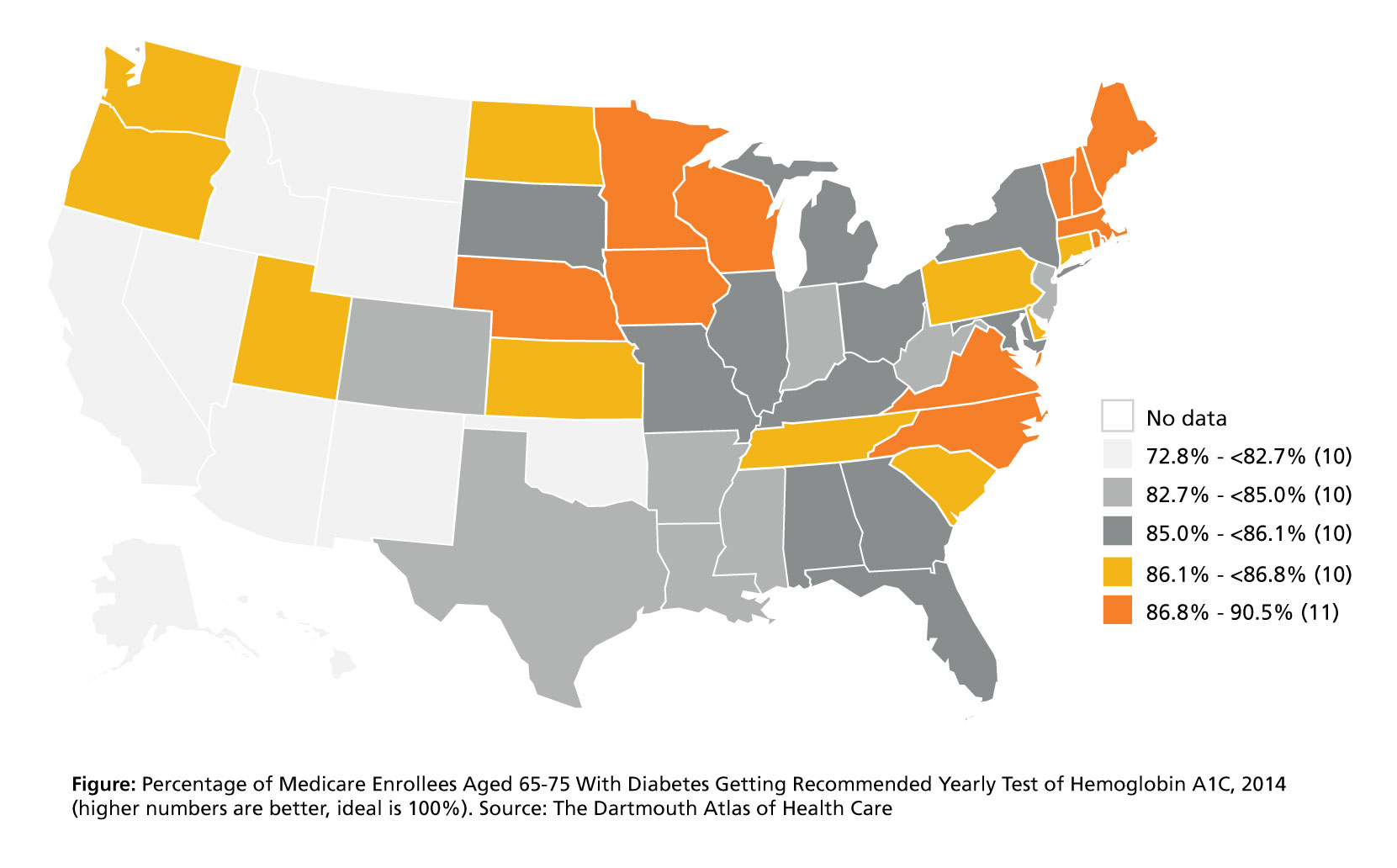

This map from Dartmouth researchers shows the striking variations in the proportion of Medicare beneficiaries getting the recommended yearly A1C testing.

There are large areas of the country where roughly 1 in 4 patients don’t get their A1C monitored once a year. If left untreated, poor blood glucose control can cause serious complications down the line, like kidney failure or blindness.

Understanding the variation in appropriate blood glucose level testing has led government health care programs and others to emphasize proper monitoring and comprehensive diabetes care through special measures. Today, insurance companies are graded — and rewarded — by Medicare on their performance with several diabetes measures. One such measure is keeping the A1C level for patients with type 2 diabetes under 8 percent. Low A1C levels mean the average blood sugar isn't too high — which is a good thing to a certain extent.

Guidelines may improve care, but sometimes there are unintended consequences

Higher quality care is everybody’s goal and driving accountability for better quality makes sense to most people. But what happens when providers focus on following these guidelines to test at least once a year and keep A1C levels low? Is it possible that a well-intentioned guideline could have some unanticipated side effects? Endocrinologist Dr. Rozalina McCoy, MD, and her research team at Mayo Clinic (OptumLabs’ co-founding partner) recently investigated this question and found some surprising trends.

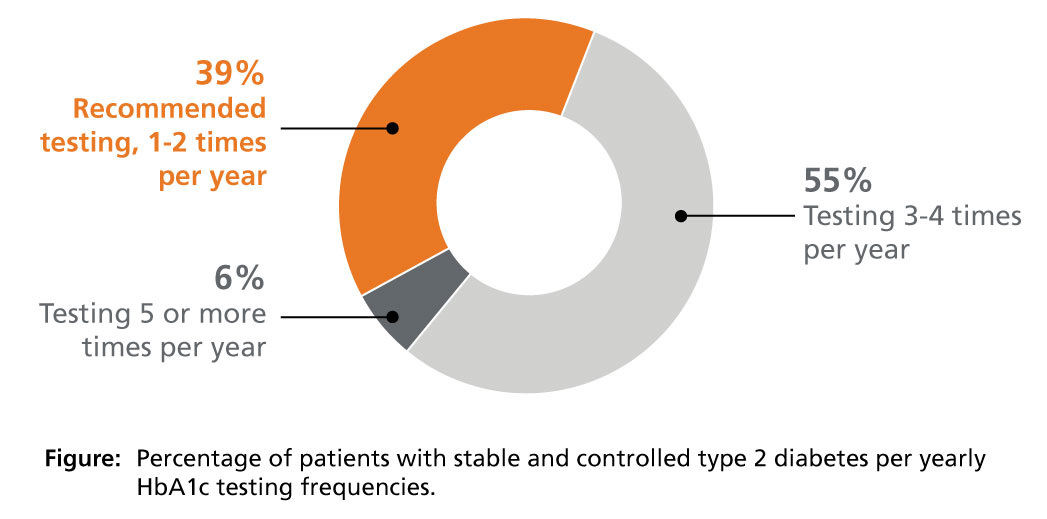

Using OptumLabs data, the Mayo team found that patients with controlled type 2 diabetes were being tested much more frequently than 1–2 times per year. More than half of patients were getting their A1C checked 3–4 times per year, and 6 percent of patients were getting 5 or more tests per year.1

When doctors test more often, they have more information about a patient’s glucose levels. This information could lead to better care, but there’s also potential this may do more harm than good.

In a follow-up study, the Mayo team discovered that more than 1 in 5 patients with controlled type 2 diabetes were likely being over treated with glucose-lowering drugs, almost doubling their risk of dangerously low blood sugar episodes (“hypoglycemia”).2 These are severe episodes that can land patients in an emergency room or hospital.

Making medical care better is a learning process. When a problem comes to light, like inconsistent A1C testing, the system responds to correct the problem by creating measures and incentives. However, unexpected side effects can emerge like over-testing that leads to over-treatment. What should we do to fix this unintended consequence?

Learning from research to improve quality measures

Upon reflection, the root of this issue is that the diabetes care measure only rewards lowering A1C levels. In collaboration with our founding consumer advocate partner AARP, OptumLabs established a new research project with Mayo Clinic to create a more nuanced performance measure that takes a “Goldilocks approach” to diabetes management.

Rather than just shooting for a low A1C, a new measure will seek to reward being “in the sweet spot” of “just right” care, so the A1C should be neither too high nor too low.

Patient’s A1C level (blood test) | Glucose-lowering drug treatment (red is unsafe, green is safe) | |

|---|---|---|

| Too low | Any medication | No medication |

| Safe range | Target regimens depend on clinical complexity, number and type of glucose-lowering medications prescribed, and other patient risk factors. | |

| Too high | ≤ 1 medication | High-intensity medication treatment |

The actual measure has multiple subcategories to address the nuanced approach required to tailor treatment for patients in different Hba1C ranges with unique risk profiles.

Mayo Clinic partners will prototype the measure using millions of de-identified patient records available from OptumLabs, and if successful, work to share this knowledge more widely with nationally recognized health organizations such as the National Quality Forum, which OptumLabs has collaborated with in the past.3

This is the blessing and the curse in the age of big data: Doctors can get a lot of helpful information to guide treatment, but the data flow can also be overwhelming. A key challenge for researchers, like those at OptumLabs, is shaping how to use the right signals to improve and not complicate treatment.

It certainly isn't easy being the pancreas, which continuously evaluates and modifies its testing and output to manage someone's blood sugar. No one can reproduce its working perfectly. But the overall example it sets — always observing, testing, responding, correcting and having a big impact on the overall system — is one that OptumLabs and our partners strive to emulate.

About the Authors

- Darshak Sanghavi, MD, is chief medical officer at OptumLabs

- Samantha Noderer, MA, is communications & translation manager at OptumLabs

References

- BMJ. HbA1c overtesting and overtreatment among US adults with controlled type 2 diabetes, 2001-13: observational population based study. Published Dec. 8, 2015. Accessed Dec. 5, 2017.

- JAMA. Intensive Treatment and Severe Hypoglycemia Among Adults With Type 2 Diabetes. Published July 2016. Accessed Dec. 5, 2017.

- National Quality Forum. NQF Launches Measure Incubator. Accessed Dec. 5, 2017.