Care after delivery: Finding opportunities to prevent diabetes in mothers

May 2, 2018

By Judith Bernstein, PhD, with Lois McCloskey, DrPH, Boston University School of Public Health

Having a baby is one of the most wonderful and, at times, difficult experiences in a woman’s life. Changes in hormones and fluid levels put a woman’s body to the test during pregnancy, requiring the body to adapt even at the cell level. In about 9 percent of pregnant women, this stress can impact the way their cells process sugar and cause a type of diabetes during pregnancy known as gestational diabetes (GDM). Women with GDM are at an increased risk for developing type 2 diabetes (T2DM) later on. In fact, up to 60 percent of women with GDM will be diagnosed with T2DM in the decade after they deliver.

Because of this risk, clinical guidelines recommend that women who have GDM during pregnancy get postpartum glucose testing within weeks after delivery and then regular blood sugar testing with a primary care doctor after that. Unfortunately, this does not always happen. This is a missed opportunity to make lifestyle changes and start medications that can prevent or delay T2DM, if initiated in time.

Our research team from Boston University School of Public Health turned to the OptumLabs data to get a big picture of what sends women along a path for diabetes prevention after GDM, or fails to do so. Our findings suggest new strategies to ensure women receive appropriate care around this important life event.

Defining the problem and opportunities with OptumLabs data

Our goal was to learn about the barriers to — as well as the opportunities to increase — postpartum glucose testing and primary care follow-up. We analyzed OptumLabs Data Warehouse claims data for 12,655 commercially insured women who had GDM and followed them for a three-year period from 2005 to 2015.

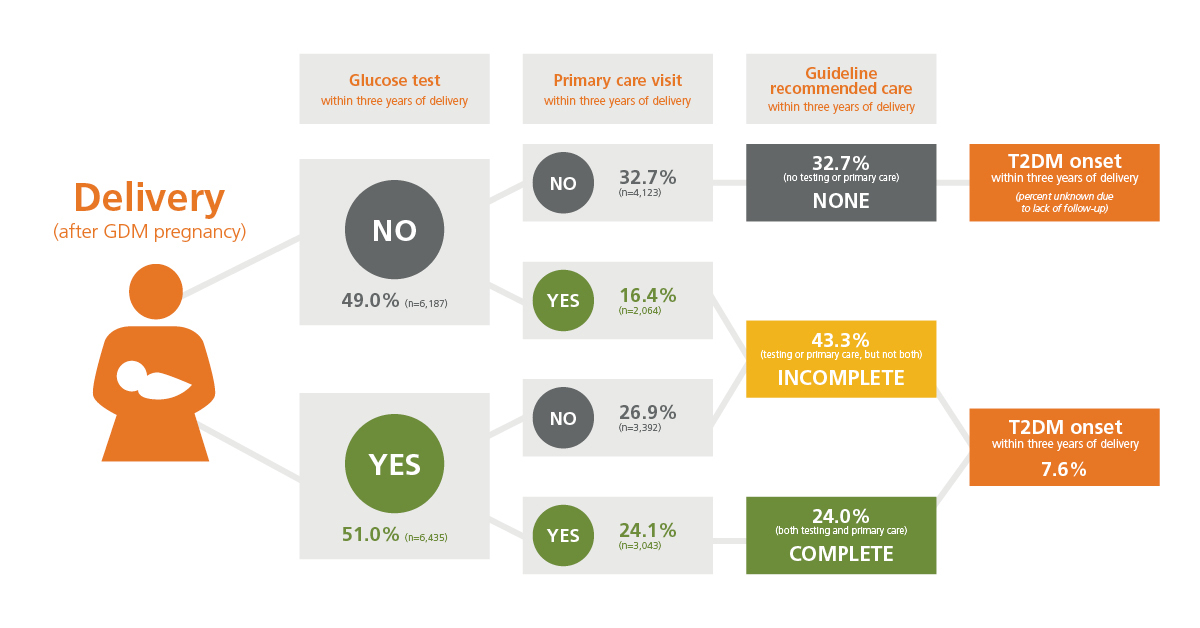

When we looked at the patterns of follow-up among these women, only 24 percent received both the recommended glucose monitoring and primary care contact. Almost half had no glucose testing, and less than half had contact with any kind of primary care after delivery. We also found a high rate of women ended up developing T2DM. You can see the breakdown of follow-up care and T2DM onset in the flow diagram below.

Figure 1. Pathways to follow-up after a GDM delivery and T2DM onset

A new T2DM diagnosis was recorded for 7.6% of the women who had follow-up within three years of a GDM delivery. Among the 32.7% of women who had no follow-up of any kind, an unknown number may have had undiagnosed T2DM or rising glucose levels.

A new T2DM diagnosis was recorded for 7.6% of the women who had follow-up within three years of a GDM delivery. Among the 32.7% of women who had no follow-up of any kind, an unknown number may have had undiagnosed T2DM or rising glucose levels.

We next looked at predictors of recommended testing and care (using a “multivariable analysis method”) and found one consistent factor: primary care. Women who visited a primary care doctor in the year before they were pregnant were 1 to 3 times more likely to receive appropriate glucose testing after delivery, as well as testing and primary care at one year. Likewise, these women were also 3.5 times more likely to get recommended testing and care at three years post-delivery.

Complex problems call for innovative, collaborative solutions

These results highlight a critical need for innovative care models that connect women with primary care from adolescence through maternity and into older age. This is especially important for women at risk for chronic illness after a pregnancy complication like GDM. Efforts should be multifocal to address patient, provider and systems barriers — in other words, “out-of-the box” solutions — solutions that build upon and leverage different kinds of expertise and perspectives.

We know that new mothers are likely busy with their newborns and, for many reasons, may not be able to focus on their own health, even for an important issue like diabetes prevention. Clinicians, too, are concentrating on immediate concerns (e.g., healing after episiotomy or cesarean section delivery), and find it hard to prioritize prevention. Can innovative solutions and opportunities help both mothers and clinicians close this gap?

Pointing the way to solutions

Our team, energized by these findings from OptumLabs data, has begun to gather a network of researchers, clinicians, patients and their advocacy organizations, health care systems designers, policy makers and communication specialists who are committed to building a better path to high-quality, coordinated and easy-to-access health care for women. We have called this effort: Bridging the Chasm between Pregnancy and Women’s Health over the Life Course. In a working conference in July 2018, invited participants from these different sectors will share their knowledge about missed opportunities to prevent downstream chronic illness after GDM and other pregnancy complications, generate ideas for potential solutions, define priorities together and issue a joint strategic plan for research and action.

Strategies that emerge from this process may include, for example:

- Streamlining referral systems to bridge the gap between obstetrics and primary care

- Bringing services directly to mothers after delivery through home glucose testing visits or technology-enabled virtual primary care visits

- Expanding the role of doulas and patient navigators to assist with follow-up testing and appointments

- Strengthening the likelihood of contact with primary care early in a woman’s life, to establish a foundation of regular preventive care that she can return to after delivery.

This effort, supported by grants from NIH-NIDDK, the Office of Women’s Health Research at NIH, and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), will field a website for sharing information, publish conference proceedings, issue a formal strategic plan and engender a new round of collaborative research and programmatic activities. Stay tuned for more on the outcomes of this network.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

- Judith Bernstein, PhD, is professor of community health sciences and emergency medicine at Boston University School of Public Health.

- Lois McCloskey, DrPh, is associate professor of community health sciences at Boston University School of Public Health.